In Groundhog Day, some unexplained force — maybe celestial, certainly moral — traps misanthropic weatherman Bill Murray in a single, repeated day until he sheds his attitude and becomes a better person. In Palm Springs, shiftless wedding guests Andy Samberg and Cristin Milioti fall into a time-loop vortex, a freak of astrophysics, in a cave. In Edge of Tomorrow, Tom Cruise and Emily Blunt battle an alien invasion for the same day over and over again after being infected with the time loop by the aliens’ blood. In Source Code, Jake Gyllenhaal is an unwilling lab rat, forced by his military superiors to run an eight-minute simulation repeatedly until he gets the right result.

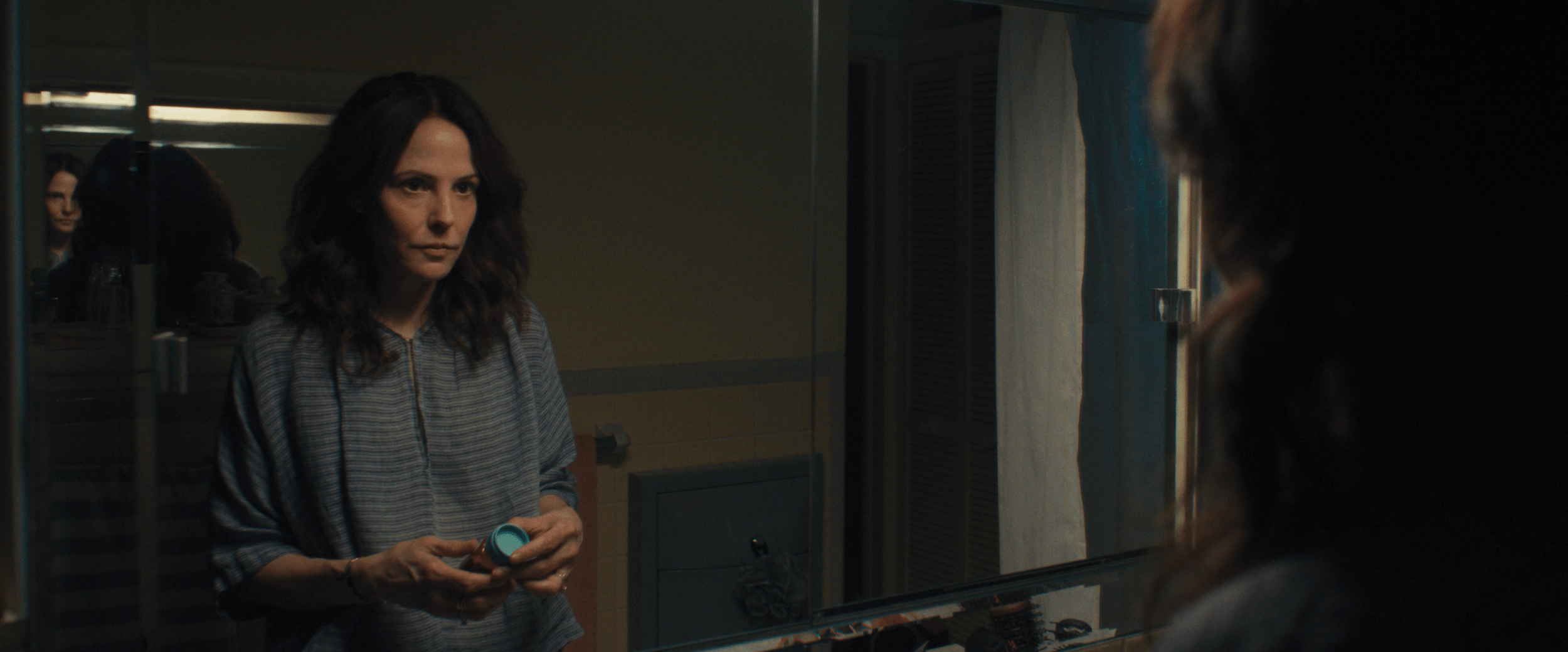

Omni Loop is a time-loop movie with an important difference. It’s not the length of time involved, although Zoya Lowe (Mary-Louise Parker) has the relatively luxurious span of a week to live over and over again. It’s a question of choice. In most time-loop movies, the characters have somehow become trapped in the loop against their will and are looking for a way out of an existential nightmare. In Omni Loop, Zoya chooses to take a pill and restart the week, every single time.

Why? Because she’s dying from a black hole in her chest. This is one of several wildly fantastical details in the otherwise normal world of Omni Loop that are treated as unremarkable by the characters; it’s a movie that inhabits a strange space between sci-fi, grounded drama, and magical realism. Another such detail is a nanoscopic man who lives, like Ant-Man, in a subatomic realm inside a perspex box, and communicates with the outside world by text message. And nobody seems to question the provenance of the bottle of time-loop pills, which Zoya remembers finding as a girl, with her name printed on the label. She suggests obliquely that she has been using the pills, which never seem to run out, throughout her life.

Is that why she is dying from a black hole in her chest? And where did those pills come from, anyway? It’s not a spoiler to say that Omni Loop does not address these questions, because if you are coming to it looking for these kinds of answers, you’re watching the wrong movie. Omni Loop writer-director Bernardo Britto is quite comfortable with his film being an overt metaphor, and hand-waving away any need to explain the plot mechanics or the sciencey stuff.

What he’s made is a quiet, moving little movie about loss, acceptance, and self-worth. Zoya is a theoretical physicist, like her husband, Donald (Carlos Jacott), but after a promising start at Princeton her career never really took off, and she has devoted at least as much of her life to her family — she has an adult daughter, Jayne (Hannah Pearl Utt) — as to her research. Now, consumed with regret at the end of her life, she keeps choosing to relive her final seven days, even as she gets frustrated and bored with her family’s sweet attempts to make them special.

A spark is ignited when she bumps into Paula (Ayo Edebiri), a lab assistant who’s carrying a textbook by Zoya. Zoya lets Paula in on the secret of her time-loop existence, and starts avoiding her family, running away from the hospital, and reintroducing herself to Paula so they can edge forward her old research. The pair are trying to reverse-engineer the pills, so she can travel back further and do something about the literal hole in her heart.

The metaphor is pretty on the nose, but if the movie works it’s because of Parker and Edebiri. Two comic actors with a lot of range and a quietly nervy edge, they’re well matched and have a great rapport; Edebiri is a warm, understated scene partner for Parker, who would be stranded otherwise, bearing the weight of an entire movie about one woman’s inner life. It’s just a shame that Edebiri’s part never quite makes sense as a character in her own right. Her motivations are either obscure or a little too emotively convenient, and the evolution of her relationship with Zoya doesn’t ring true considering she’s constantly meeting her for the first time.

The real joy of Omni Loop is seeing Parker take on such a substantial role. You probably remember her as the suburban mom turned pot dealer in Weeds, always slurping absently on a giant iced coffee, saucer eyes flashing a mercurial mixture of bafflement, sardonic remove, and girlish glee. She’s a vivid screen presence and a great actor, and she draws what might otherwise be a rather pat end for Zoya’s story out into something honest and touching.

Omni Loop takes its name from a spur of the Metromover transit system in Miami — an elevated, automated monorail system from the 1980s that now looks kind of retro-futuristic. Britto shoots scenes of the characters on these trains to accentuate the movie’s subtle, faded sci-fi aesthetic. But the futurism of the title doesn’t really suit the movie; it’s no dystopian exploration of time and identity like Source Code. Nor is it interested in exploiting all the dramatic and comic variations (never mind the philosophical and ethical implications) of being stuck in time like Groundhog Day does. Its time loop isn’t an existential trap or a satirical device.

Omni Loop uses the repetition in a more intimate and psychological way; it’s a time-loop movie for the therapized age. Britto’s ambitions are smaller, and the movie is vague at times. But in the end, thanks to Parker, it does succeed in getting to an emotional truth about a person who gets stuck facing up to perhaps the hardest thing a person can face: the end, and the resulting reckoning with all that came before.

Omni Loop is in theaters now.